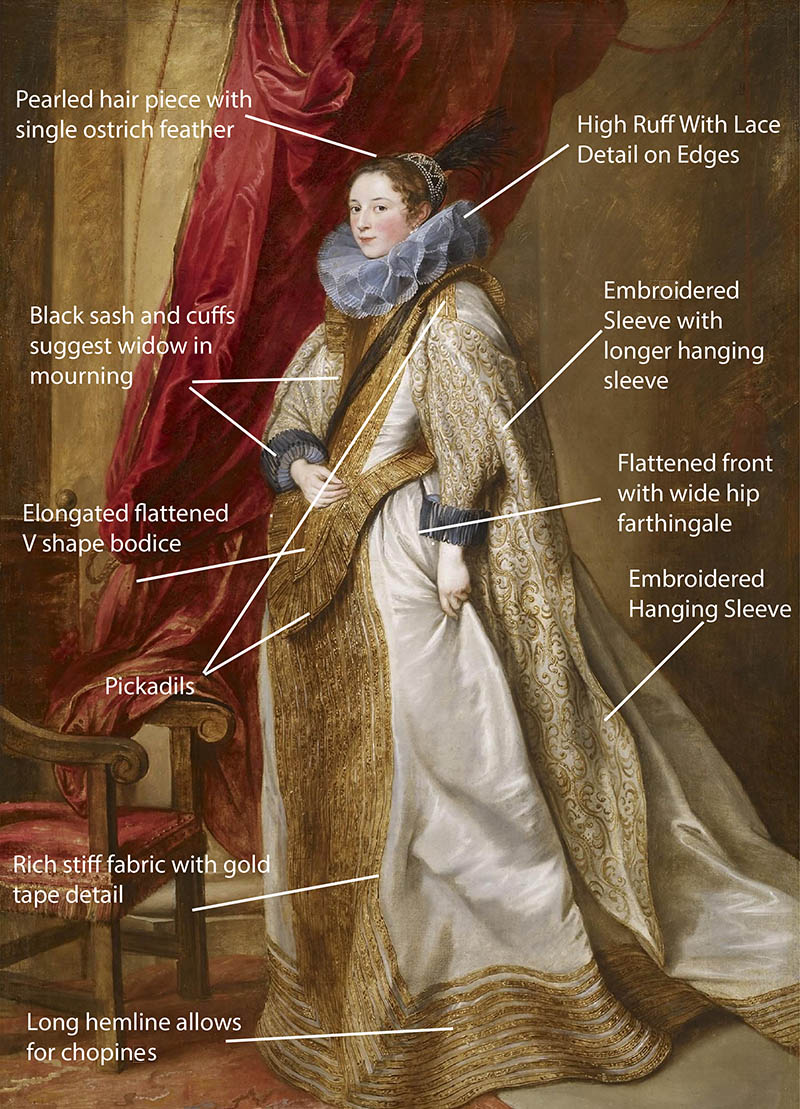

The Genoese Noblewoman (1625-1627) painted by Anthony Van Dyck reflects dress trends of the early 17th century, particularly in the region of Genoa, such as rich silks ornamented with metallic lace, starched ruffs and the deep “V” shaped bodice.

About The Portrait

F

lemish artist Anthony Van Dyck (Fig. 1) painted a great many portraits in his short life in England and Italy – mostly Genoa – as art historian Michael Jaffé explains. From the age of ten, Van Dyck studied with Peter Paul Rubens. Rubens also spent many years in Genoa and the influence of the master is highly evident in Van Dyck’s works. Perhaps it was young Van Dyck’s artist father or the family’s history in the silk and embroidery business that gave him such a natural understanding and comfort in rendering fabric and costume detail (Jaffé 1-2).

Van Dyck’s ability to translate the conversation between light and fabric is evident in his portrait of the Genoese noblewoman. In this portrait, every pleat, stitch and gather seems to glisten. When compared to Van Dyck’s other Genoese portraits, it contains very similar light, architecture and level of formality, so much so if one were to line all of his Genoese portraits next to another, it would appear the families could very well be occupying the same room. As Christopher Brown notes in Van Dyck (1983):

“The background is suggested, not described – Van Dyck’s hasty brushstrokes can easily be made out – and is deliberately contrasted by the painter with the careful, even painstaking rendering of the figure of the Marchesa herself.” (87)

It is this consistency that made him a highly sought after portraitist of aristocratic Genoese families.

Though the names of the families which Van Dyck painted are known, there is some scholarly debate as to the Genoese noblewoman’s true identity. According to the Frick Collection, the young woman is unknown, though the black lace on her cuffs suggests she is a widow. Brown identifies the young woman as Paola Adorno, Marchesa Brignole-Sale who is know to have sat for the young artist on least three other occasions (86). It is not hard to imagine why some may come to this conclusion. If one compares this portrait to his 1627 painting of Marchesa Paolina Adorno Brignole-Sale (Fig. 2), they are undeniably similar. The Marchesa wears almost the same dress, though in blue. The pose and setting are also almost identical. The only differences that are evident is the parrot on the chair and the flower she is holding.

Still, the name of the lady remains an uncertainty. What we are sure of is that she was someone of high social status. The Frick’s audio guide explains Van Dyck’s approach to his subject. The artist elongated the body and put the viewer just below the gaze of subject, so that one feels as though they are looking up at this vision of nobility. This strategy is seen in all of Van Dyck’s portraits and contributed to his appeal as an artist to the nobility.

Fig. 1 - Anthony Van Dyck (Flemish, 1599-1641). Self-Portrait, 1640. Oil on canvas; 56 x 46 cm (22 in x 18 1/8 in). London: National Portrait Gallery, NPG 6987. Source: National Portrait Gallery

Fig. 2 - Anthony Van Dyck (Flemish, 1599-1641). Marchesa Paolina Adorno Brignolo- Sale, 1627. Oil on canvas; 288.5 x 199 cm (113.5 x 78 inches). Genoa: Galleria di Palazzo Rosso. Source: Wikipedia

Anthony van Dyck (Flemish, 1577–1640). Genoese Noblewoman, ca. 1625-27. Oil on canvas; 230.8 x 156.5 cm (90 7/8 x 61 5/8 in). New York: The Frick Collection, 1914.1.43. Henry Clay Frick Bequest. Source: The Frick Collection

About the Fashion

There is strong Spanish influence in this portrait. The noblewoman is wearing a flat-front style farthingale with wider hips than previously, usually constructed of whalebone hoops. Though open-front overskirts and U-shaped stomachers are being introduced throughout Europe, the noblewoman has yet to adopt these trends. Her high neckline suggests Genoa may still be resisting against the low necklines of the mid 16th century (Tortora 218). The bodice has a triangular shape with a very low and flattened V-bodice. She’s also wearing black, white and gold, which is a palette more prevalent in Spanish costume. Her sleeves are embellished with a gold scroll design (likely a silk brocade) and emerge out of long flowing hanging sleeves. She is very elongated in silhouette and is perhaps wearing chopines for height under her very long hemline.

As the Frick notes, she was most likely a widow as her black sash across the bodice and black lace cuffs suggest. The ruff is quite sheer, perhaps made of silk, heavily starched holding wide ruffles and has a lace trim along the edges. The ruffled cuffs have a black trim along the edges. The dress is a stiff opulent white silk with gold metallic lace trim along the bottom and front. Golden pickadils create a small peplum off the edge of the bodice and also on the shoulders.

Her ornately jeweled hairpiece with black ostrich feather also suggests that she was at some point married, as her hair is tied up and not free-flowing. Though she doesn’t wear a love lock, her curls romantically frame her face.

Though in 1625, the noblewoman isn’t obscenely outdated, she does appear to be embracing the more conservative trends perhaps because she is nobility and also potentially a widow. When compared to Ruben’s portrait of his wife, Helene Fourment in her Wedding Dress (1630) (Fig. 3), one notes Fourment’s softer silhouette and exposed décolletage, but one must bear in mind the difference of society and country. To analyze how fast this region shifts in trends, one can compare the Genoese Noblewoman (1625-1627) to Rubens’ earlier Marchesa Brigida Spinola Doria (1607) (Fig. 4). Within twenty years, the bodice dropped to the deep V-shape, the farthingale flattened and the ruff became smaller. She may in later years adopt Fourment’s low-squared neckline and virago sleeves, but as of 1625 she may have wanted to maintain the ornate regality of her station and the previous years’ fashions.

When the region is put into context, the young woman is right on trend, as Genoa maintained the Spanish style for a bit longer than Britain or the Netherlands (Gordenker). This is evident as shown by other Genoese portraits around the same date. The metallic lace edged silk dress design was very popular as it is seen in a number of Genoese portraits; for example, the Portrait of Caterina Balbi Durazzo (1641) shows almost the same dress in black (Fig. 5).

Even the little girl in the portrait, Geronima Sale Brignole with her Daughter Maria Aurelia (1625) (Fig. 6), seems to be wearing a smaller version of the noblewoman’s dress. All Genoese women shown are dressed in stiff luxurious cascading fabrics, low V-bodices with exaggerated ruffs. Van Dyck also used the color of dress to depict clues about the lives of his subjects, for instance the widowed mother is engulfed in black satin (Fig. 7), which also supports the implications of the young noblewoman’s black lace cuffs and sash.

Thanks to Van Dyck’s detailed representations, the trends in early 17th century Genoese fashion are clear.

Fig. 3 - Peter Paul Rubens (Flemish, 1577-1640). Helene Fourment in her Wedding dress, 1630. Oil on oak; 28 x 32.7 cm. Munich: Alte Pinakothek, 340. Source: Alte Pinakothek

Fig. 4 - Peter Paul Rubens (Flemish, 1577 - 1640). Marchesa Brigida Spinola Doria, 1606. Oil on canvas; 152.5 x 99 cm (60 1/16 x 39 in). Washington: National Gallery of Art, 1961.9.60. Samuel H. Kress Collection. Source: National Gallery of Art

Fig. 5 - Anthony Van Dyck (Flemish, 1599-1641). Portrait of Caterina Balbi Durazzo, 1624. Oil on canvas; 220.2 x 149 cm. Genoa: Palazzo Reale Di Genova. Source: Restituzioni

Fig. 6 - Anthony Van Dyck (Flemish, 1599-1641). Portrait of Geronima Sale Brignole with daughter Maria Aureli, 1627. Oil on canvas; 226.3 x 151.8 cm. Genoa: Musei di Strada Nuova. Source: Google Arts & Culture

Fig. 7 - Anthony Van Dyck (Flemish, 1599-1641). A Genoese Noblewoman and Her Son, 1626. Oil on canvas; 191.5 x 139.5 cm (75 3/8 x 54 15/16 in). Washington: National Gallery of Art, 1942.9.91. Widener Collection. Source: NGA

References:

- Brown, Christopher. Van Dyck. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1983. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/801979537.

- Brown, Christopher, and Hans Vlieghe. Van Dyck, 1599-1641. New York: Rizzoli, 1999. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/847455426.

- Frick Collection. “Genoese Noblewoman by Anthony Van Dyck.” collections.frick.org, n.d. https://collections.frick.org/objects/159/genoese-noblewoman.

- Gordenker, Emilie E. S. Anthony van Dyck (1599-1641): And the Representation of Dress in Seventeenth-Century Portraiture. Turnhout, Belgium: Brepols, 2001. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/50714021.

- Jaffé, Michael. “Dyck, [Dijck] Sir Anthony [Anthonie; Antoon] Van.” Oxfordonline.com, 2003. http://www.oxfordartonline.com/groveart/view/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.001.0001/oao-9781884446054-e-7000024345.

- Tortora, Phyllis G., and Sara B. Marcketti. Survey of Historic Costume. Sixth edition. New York, NY: Fairchild Books, 2015. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/910929404.